The Short Man

YEAR: 1988

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 18

PROVENANCE

The artist

2000, The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, USA

EXHIBITIONS

New York, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

Ten Characters 30 Apr 1988 — 4 Jun 1988

London, Institute of Contemporary Art

Ilya Kabakov. The Untalented Artist and Other Characters at the ica London 23 Feb 1989 — 23 Apr 1989 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters)

Zurich, Kunsthalle Zürich

Das Schiff – Die Kommunalwohnung, zwei Installationen von Ilya Kabakov 2 Jun 1989 — 30 Jul 1989 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters)

Washington, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Directions. Ilya Kabakov. Ten Characters 7 Mar 1990 — 3 Jun 1990 (as part of No 15, Ten Characters)

Hamburg, Deichtorhallen

Ilya Kabakov. Der Lesesaal – Bilder, Leporellos und Zeichnungen 19 Apr 1996 — 8 Jul 1996 (as part of No 90, The Reading Room)

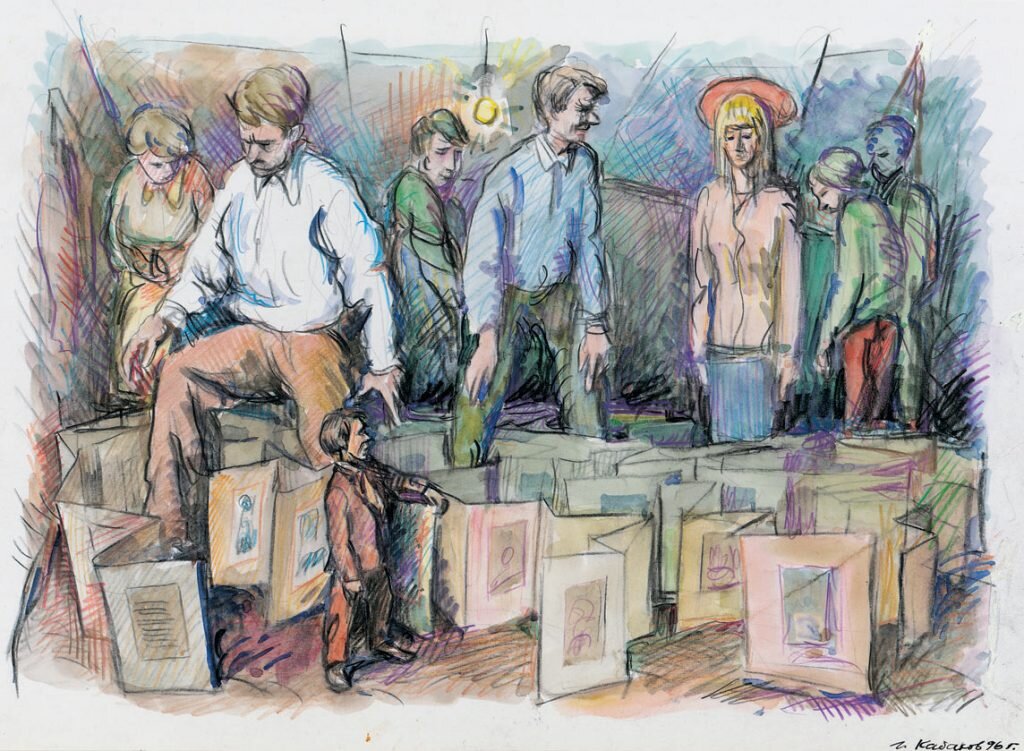

DESCRIPTION

He was short and it really bothered him that others were taller and even a lot taller than he was. “If only they would walk in a squatting position,” he thought, going to our communal kitchen with a feeling of vexation and glancing at the tall Nikolai Matveevich from the corner room. But how can I make them do this? For they won’t do it just because I ask them to. An unexpected incident helped him in this dilemma. Everyone in our apartment knows that when it’s Sokolov’s turn to clean, it was more like a performance than a simple cleaning. He doesn’t miss one scrap of paper, not one rag, not one match-stick, everything would be scrutinized very carefully, investigated, and carried away to his room and hidden.

And so it was on this occasion. When the short man entered the kitchen, all kinds of various junk – screws, spools, matches – were already laying in special boxes and jars, and Sokolov himself, on his hands and knees, read something from the lid of a mayonnaise jar which he had swept out from under the stove. “This is just what I need!” – was the thought which suddenly flashed through the short man’s mind. “They have to read something, look at something right near the floor.” But what could be located so low? Not garbage, which could only interest Sokolov!

He began to think about what could make adults, busy people, spend time bending down to the floor. Memories of his distant childhood came to mind. He saw himself on his knees in front of a big palace with many towers and other decorations that he and his brother had glued together out of cardboard, paper, and pieces of wood. There was a big courtyard in the castle, and they, like Gulliver’s, would step across the wall with embrasures, and wage battles with tiny knights inside the yard. Leaning over from above, it was possible to see all that was happening in the main tower, in the throne room, and in the queen’s room…

This recollection prompted the following idea. What would happen if you built a similar castle – of course not like the one in his childhood, since it was unlikely that adults would find the time to lean over and look into it, but something resembling a labyrinth to fill the entire room with its walls covered with drawings and inscriptions – and you could look at these pictures and read these inscriptions only by bending down? From above it would remind one of an entire city, and you could walk through it, stepping over the walls and streets, but you could look inside and see the details only by bending down.

Now he only had to figure out what to use to make this city-labyrinth. The engineering task, so to speak, was that it must be possible for such a labyrinth to be assembled shortly before the arrival of guests, and just as easily disassembled. Another problem was how and where to store the labyrinth since there wasn’t any extra space in the room at all.

As a result of long considerations, he came to the conclusion that the basic element of this ‘labyrinth’ should be a screen, an ordinary children’s screen-book published by our publishing houses for children. Of course, the content of the screen should be different. All the pages would comprise a unified story, so that the viewer, bending down, could follow it along the entire length of the screen. Furthermore, this kind of screen folds up easily and can be stored like an ordinary book, and when it was necessary, you could quickly unfold it and set it up around the room.

The more he thought about his project, the more he liked it. It was easy and simple to make such a screen: all you needed was a little glue, paper, cardboard, ordinary book-binding to form hinges between the leafs, and it was ready. Nor was it difficult to think up a subject – when he was young he used to write pretty good short stories, and he even illustrated them himself. It’s a shame that they weren’t accepted for publication when he would take what he thought to be finished books to the publishing house: go ahead and print it, but you’ll have to pay for it!

And so, he set to work! He was immediately carried away by his work. He spent entire evenings gluing, cutting, drawing, writing, and finally, his idea began to come to life. There were more and more screens, tiny ones and long ones, consisting of 6-8 panels and 10-14 panels of the most diverse content. When he would arrange them on the floor, at first they only took up a part of his half-empty room, which contained only a small table and a cot where he slept. Then they took up half the room, and, finally, the entire room. There were tall and short ones, bright and dull ones, covered with drawings or texts. They really did resemble a big city, and the author himself would walk around the room, as happy as a child, with a lamp illuminating first this and then that part … But then when the work was coming to an end and the entire room was already full to the point that there was no free space left in it, even then it would seem to him, like before, that one very important detail was missing, some essential stroke that would perfect his entire concept. Having thought about it, he decided that he had to make one more screen, a super screen, so to speak, which would surround and enclose the labyrinth. But what should be depicted on it? If it was a story, then it would have to be extraordinarily long, almost a novel, for a screen engulfing all the rest would have to have a length of not less than 40 meters. And what plot should he choose?

“Here I am searching for an answer, and it’s right under my nose!” he hit himself on the head. “Everything that goes on in our communal kitchen is not just a plot, but a ready-made novel! If you were to recall and write down all of the phrases which have resounded here all these years, you would get not one, but many detective stories!” He began to recall these phrases, and they literally began to ring in his ears. Here there were conversations about how to make eggplant caviar, discussions about the latest film, and arguments about taking out the garbage, and curses, and tears, and fights … He decided to glue phrases individually on pieces of wall-paper glued to cardboard. In the spaces between the separate pieces of paper, he arranged photographs of the kitchen and other ‘communal conveniences’: the toilet, the bathroom, the ‘common room,’ i.e. the storage area. It took him almost three months to make this screen, since he didn’t type these phrases but wrote them out by hand, meticulously forming, almost drawing each letter. But when the ‘big screen’ was finally ready, having set up his labyrinth of 10-16 screens and surrounded them on all sides by the ‘big’ one, and he looked over everything as a whole, he understood that the work was finished and that he could now invite viewers.

First, he decided to invite his co-workers (he worked as an accountant at a textile depot). Among them, Nikolai Ivanovich was, as it seemed to him, especially tall, and he anticipated with pleasure how this person would hunch up as he looked at the smallest screen. The guests were, of course, invited to come in the evening after work, and in the morning before he left he carefully set up his entire labyrinth. With complete satisfaction, he set out for work, locking the door behind him. Having singled out and invited a few co-workers in the morning, he was in a state of extreme excitement all day, anticipating what effect his exhibit would have, and he was happy that his plans were finally being realized.

After work, a small group set out for his place, secretly counting on a tasty and satisfying dinner, otherwise why would anyone invite guests with such a secretive and enigmatic look? The key rattled in the lock, the door opened and everyone was invited to enter. But by the confused and irritated look of his guests, he understood instantly that what he had counted upon happening was not meant to be. The guests simply started to step over the objects that had been placed in their way, not paying any attention to them at all, considering them to be ridiculous and incomprehensible obstacles, perhaps trash which the muddle-headed host, who didn’t know how to receive guests at all, had forgotten to take out. To his disappointment, not one of the guests bent down, and all of them, stepping with great difficulty over the scattered obstacles, like giants, dispersed to the corners. There was no table set for dinner, no meal was in sight, and everyone began to look at the walls, thinking about what to do. But there was nothing special or interesting on the walls. Two or three photographs hung on nails, and to the left of the door, hung two shirts and a gray suit, also on nails driven into the wall. The host was dispiritedly silent. It was getting more and more difficult and awkward to step over the paper fences that had been arranged in all directions. The guests were bored and gradually began to say good-bye, blaming it on the arrival of two nephews and transportation difficulties. The host, completely downcast, didn’t try to detain them. The elderly woman, also an accountant, who sat at the desk next to him at work, said that she had had an interesting time at his place, that as she understood it, he wrote short stories and she would like to read them, but because of her bad legs, she couldn’t bend down. By the way, one of the neighbors in her apartment studied literature, and perhaps it would be interesting for him to read all this. She asked his permission to tell him about what she had seen.

A few days later there was a telephone call. A quiet, polite voice, having stated his name, asked if he could stop by and look at the ‘work.’ The room had been cleaned up a long time ago, and the ‘exhibits’ had been carefully put away in boxes. The ‘master’ of the room told the caller all this, thinking about this unknown visitor with animosity. The things had been put away, but if someone wanted to see them, then he could give them a few to take home. What he heard on the other end of the line surprised him terribly. He was asked to set up everything exactly as it was before his guests had arrived. “Just exactly like it was the last time,” said a thin, high voice. They arranged to meet, and at the appointed hour the new guest entered the room which had been prepared for his visit just exactly as it had been the time before. This time everything was different, and the result was exactly the one that he had anticipated from the very beginning. All his calculations turned out to be correct, and the new guest, crying out in amazement, fell to his knees and began to read and examine, to move along the arranged screens, not missing a single drawing, not a single text, not even the smallest detail. It all invoked in him bold delight and astonishment. He was thrilled with both the concept and the execution, and at times he leaned over so low, that his head wasn’t visible at all over the screens. He even said that this entire work should be placed in a museum, he just didn’t know which one, he promised to think about it and to do something. In short, the success of the undertaking was total and definitive.

There was just one little ‘but’ in this accomplishment, only one thing spoiled the meticulously conceived and ultimately achieved success, only one thing interfered with total satisfaction in the triumph. The guest himself was short, almost tiny, just like the host, who noticed this with vexation when the guest had barely stepped off the bus at the stop where they had agreed to meet before the visit.

ARTIST`S COMMENTS

Always, as long as I can remember, I felt I was nonexistent, minuscule, and insignificant. This is not merely a matter of the well-known ‘inferiority complex.’ I have been familiar with almost all types of this complex since childhood, no matter how vague and poly-semantic. But I would like to tell in detail about one of the many sides of this very complex – about the insignificance, foolishness, primitiveness of everything, no matter what this subject undertook, no matter what he began…

Everything I did seemed to me wretched, unimportant, uninteresting, all of my ideas were doomed to failure.

“He didn’t get his share of love in childhood.”…

I consciously remember myself from the age of 10-11; but much earlier, at 9-10 years old I moved into a dormitory. There were eight people in our ‘bedroom,’ 75 total in the boarding school, and we literally spent all our time under each other’s noses: in the morning, during classes and after classes, when we returned to 158 the halls of the boarding school and the bedrooms. We also went to eat lunch in the cafeteria all together, and we would fall asleep to the voices of our roommates who hadn’t fallen asleep yet.

And, of course, every day each of us encountered the ‘gods’ chosen one,’ an example of a happy fate, who had become a great artist, a genius. Even though he was our age, he lived among us, simple mortals, but for him, a place was already waiting among the great artists of the past. The world of the boarding school, of the art school, was a closed universe for us: we didn’t know any other, non-school world; we had only the vaguest notion of it. He was perfection; a talent recognized by all – by both us and the teachers – he was for us a unique idol, a real, live ideal of an artist. As I remember, he was endowed with the entire spectrum of artistic qualities: he had a wonderful sense of color, an extraordinary imagination, perfect composition, virtuoso execution, and in life, he was always cheerful, responsive, benevolent, and simple. All of his drawings invoked admiration. They hung not only in the halls of the school (where school masterpieces had the right to hang) but also in the library, in the teachers’ room and even in the director’s office. In this way, they were connected to the higher world of absolute treasures, like the reproductions of paintings by Titian, Rembrandt, Raphael, which were kept in the same place…

These ‘chosen ones of fate’ (there were a few in our school) and their creations plunged me into deep despair as soon as I would turn to my own works. My works – gray, dull, deprived of any spark of talent – were forced, and from adjustments and corrections, they became completely ridiculous and useless. None of my classmates looked at them, and I could feel that the teachers, who would walk around the class during our lessons tried not to notice either them or me.

But, my Lord, how could I attract attention to these works that were useless to me and to others? Not by means of correction, improvement, further immersion into the secrets of the craft (they were ‘forbidden’ to me, I knew this), not via development of a ‘natural gift’ (I didn’t have any), not via ‘love for art’ (I didn’t experience such love).

Everything listed above, I repeat, was beyond my capability. I had to find some sort of special trick, a special ‘move’ to bypass that which was presented as the real path to becoming a ‘genuine artist’ and to emerge on the outside via some quick, abrupt, unexpected, heretofore unseen means. I didn’t know such a means.

Images

Literature